Archaeology of the Wren Garden

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1760

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2015

Archaeology of the Wren Garden

July 2014

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

| List of Figures | 5 |

| Foreword | 7 |

| Introduction and Project Description | 9 |

| Acknowledgements | 13 |

| Historical Background | 15 |

| Research Strategy | 15 |

| Data Limitations | 16 |

| Historical Overview | 16 |

| Previous Archaeology | 27 |

| Field and Laboratory Procedures | 33 |

| Sampling and Excavation Procedures | 34 |

| Laboratory Methods | 35 |

| Excavation Description and Results | 37 |

| 2004-2005 Testing Strategies | 37 |

| Geophysical Survey | 37 |

| Test Units | 39 |

| 2005 Excavation Block | 44 |

| Methodology and Rationale for Location | 44 |

| Sampling and Excavation Procedures — 2005 | 45 |

| Twentieth-Century Features | 46 |

| Stratigraphy of the Excavation Block | 49 |

| Subsequent Interpretation of 2005 Stratigraphy | 53 |

| Ambiguous and Possible Colonial Features | 53 |

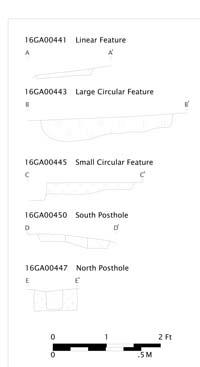

| Linear Features | 56 |

| Postholes | 58 |

| Drainage feature/brick crumb concentration | 58 |

| Artifacts | 58 |

| Interpretation | 59 |

| Additional Testing, October 2005 | 63 |

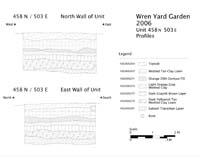

| 2006 Excavation Block | 66 |

| Methodology and Location Rationale | 66 |

| Page 4 | |

| Twentieth Century Features, Disturbances and Incompletely Excavated Units | 67 |

| Pre-twentieth Century Features | 68 |

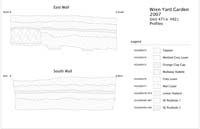

| 2007 Excavation Block | 74 |

| 2006-2007 Excavation Block Locations | 74 |

| Twentieth-century Intrusive features | 75 |

| Eighteenth-Century/Bodleian Plate Design Features | 81 |

| November 2007 Supplemental Unit | 85 |

| Summary of Results | 86 |

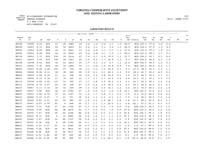

| Laboratory Analysis and Student Projects | 87 |

| Environmental/Archaeobotany | 87 |

| Documentary Research | 88 |

| Mapping and Landscape Studies | 88 |

| Conclusions and Recommendations | 91 |

| Bibliography and References | 94 |

| Appendices | |

| 1. Archival Record — Jessica Way | |

| 2. Artifact Inventory, in separate volume | |

| 3. Geophysical Survey — Bruce Bevan | |

| 4. Context Records | |

| 5. Soil Chemistry | |

| 6. Geometry of the Wren Yard — Benjamin Skolnik | |

| 7. Additional Drawings | |

| Figure 1. Bodleian Plate, Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK | 10 |

| Figure 2. Detail of Desandroüins Map (1781) | 11 |

| Figure 3. Detail of Simcoe Map (1782) | 11 |

| Figure 4. College Building 1702, Franz Ludwig Michel, Bergerbibliothek, Bern, Switzerland | 12 |

| Figure 5. Detail of St. Simone Map (1781) | 23 |

| Figure 6. Detail of Berthier Map (1782) | 23 |

| Figure 7. Wren Yard Garden, Previous Archaeology, All Explorations Prior to 2005 | 29 |

| Figure 8. Detail of Previous Archaeological findings in the region of the President's House | 30 |

| Figure 9. Detail of Previous Archaeology to the West and South of the Wren Building | 31 |

| Figure 10. Context Record Sheet — CWF | 36 |

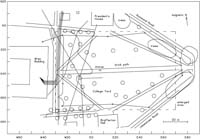

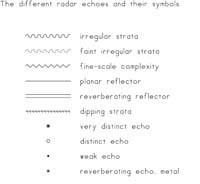

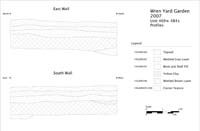

| Figure 11. Composite Geophysical Drawing | 37 |

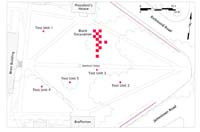

| Figure 12. Test Unit and 2005 Block Unit locations | 39 |

| Figure 13. Test Unit 1 — North sidewall | 40 |

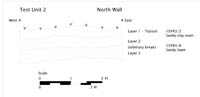

| Figure 14. Test Unit 2 — North Sidewall | 41 |

| Figure 15. College Building c. 1856 (CWF) | 42 |

| Figure 16. Test Unit 3 — North Sidewall | 43 |

| Figure 17. Completed 2005 Excavation Block (CWF) | 44 |

| Figure 18. 2005 Excavation Block — 20th-Century Features | 47 |

| Figure 19. Student Brian Davis and Burnt Fill Deposit (CWF) | 48 |

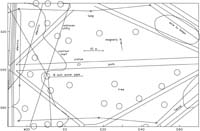

| Figure 20. Summary map of the 2005 Excavation Block showing all features | 49 |

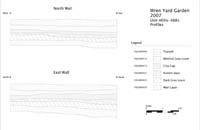

| Figure 21. Profiles of Unit 498N/508E | 50 |

| Figure 22. Harris Matrix — 2005 Block | 52 |

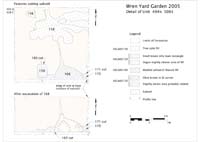

| Figure 23. Detail Plan of Unit 494N/508E | 54 |

| Figure 24. Detail Plan of Unit 490N/516E | 55 |

| Figure 25. "Yellow Loam Trench", Linear Feature 1 | 56 |

| Figure 26. Profiles of Unit 486N/512E | 57 |

| Figure 27. Overall of 2005 Block. Pre-20th-Century Features | 60 |

| Figure 28. Location of 2005 Block and Test Units | 63 |

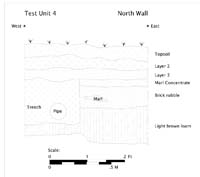

| Figure 29. Detail Plan of Test Unit 4 | 64 |

| Figure 30. Profile of North Wall, Test Unit 4 | 64 |

| Figure 31. Profile of North Wall, Test Unit 5 | 65 |

| Figure 32. Location of 2006 Excavation Units | 67 |

| Figure 33. Brick rubble layers with thin, continuous ash layer in-between | 68 |

| Figure 34. Plan view of Later Marl Walkway as excavated in 2006 | 69 |

| Figure 35. Cannon Balls in situ | 69 |

| Figure 36. Plan view of Cannonball Layer | 70 |

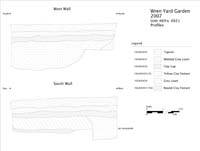

| Figure 37. Profiles of Unit 449N/478E | 71 |

| Figure 38. Plan of Planting Features along south edge of 2006 excavation | 72 |

| Figure 39. Major Features in the 2006 Excavation Block | 73 |

| Page 6 | |

| Figure 40. Location Plan of 2006 and 2007 Excavation Blocks | 75 |

| Figure 41. Profiles of Unit 453N/480E | 76 |

| Figure 42. Plan View of later Marl walkways | 78 |

| Figure 43. Excavation of Diagonal Walkway Fill #2. Note faunal remains intact. (CWF) | 79 |

| Figure 44. Plan View of Earlier Diagonal Walkway 2 | 80 |

| Figure 45. Detail of Bodleian Plate | 81 |

| Figure 46. 471N/490E — Unexcavated Features | 82 |

| Figure 47. Plan View of Unit 471N/490E and later Unit 471N/492E | 83 |

| Figure 48. Profiles of features in unit 471N/490E | 83 |

| Figure 49. Photograph of likely topiary planting hole 16GA-00405/406 in Unit 469N/484E | 84 |

| Figure 50. Close-up of Garden Features in 2007 Excavation Block 2 | 84 |

| Figure 51. 471N/492E — Plan of Excavated Features | 85 |

Foreword

The reader should be excused for assuming that the oldest and most prominent landscape at the College of William and Mary has been fully studied, and that its evolution is well-understood. This report both charts the yawning limits of what is known and begins to answer central questions about development of one of British North America's most important public landscapes. The College's first and largest early building, now called the Wren Building, preceded the establishment of Williamsburg in 1699, and it has anchored the west end of the town's principal avenue ever since. Its dramatic setting has often been graphically portrayed, most memorably in the c.1740 copper engraving plate found in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. This so-called Bodleian Plate shows a formal, open landscape with carefully-orchestrated ornamental plantings, in stark contrast to the present picturesque, heavily-wooded College yard.

It is only in recent years that we have begun to understand the degree to which the pre-Revolutionary campus was a controlled precinct, mirroring those at the Governor's Palace and Capitol, and how dramatically it changed after 1781. Unlike the Palace gardens and walled Capitol yard, now substantially excavated and restored, the College yard remains relatively intact archaeologically. Steven Archer's report, completed in 2014 with help from Andrew Edwards, contributes significantly to that understanding. It demonstrates that landscape elements shown on the Bodleian Plate existed, contributes detail about their form, and raises useful questions about how and when they developed. It also makes apparent the value of both excavating other areas of the yard and protecting it as an archaeological resource of much consequence. This and subsequent excavation around the adjoining Brafferton reveal that below-ground remains are rich but extremely delicate, worthy of gentle handling by future landscaping crews and archaeologists alike.

This three-year project would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support and generous funding provided by Suzann Wilson Matthews '71. We thank the College for the opportunity to study the Wren Yard, especially Louise Lambert Kale, Director of the Historic Campus, who commissioned the work.

Edward A. Chappell

Shirley and Richard Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research

Chapter 1

Introduction and Project Description

The intent of the 2004-2007 Wren Garden archaeological testing and excavations project was to characterize and determine what, if anything, remains of the formal landscape design of the College of William and Mary's historic campus, installed with the initial construction of the Wren Building beginning in the late seventeenth century. The project was primarily focused on the formal gardens east of the College that would have been the 'face' of the College to Williamsburg as it transformed from Middle Plantation to the colonial capital of Virginia beginning in 1699.

In addition to being a research project, the archaeological process has involved students of the College of William and Mary to a remarkable degree as an educational and pedagogical experiment. In partnership with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, undergraduate and graduate students not only participated in excavations during three summer field seasons, but also developed and addressed ancillary and supporting research projects, learned laboratory and analysis skills, and contributed to the interpretation of the project through follow-up courses conducted after each excavation season. To a large degree, the analysis reflects the questions present-day students at William and Mary wanted answered about their forbearers from previous centuries. As the modern archaeological profession endeavors to better incorporate indigenous and descendant communities in their practices, the Wren Garden excavations offer a unique perspective on this goal, where an educational institution forms the focal point of a culture that has evolved significantly over more than three hundred years.

As an archaeological project, the excavations have been limited to a boundary definition and site characterization program rather than the broad, open-area exposures typical of most Chesapeake historical archaeology (e.g., Noël Hume 1991). Because the College Yard is not a threatened resource, the overarching goal has been to do "more with less" by excavating minimally but doing more intensive data recovery (flotation, specialized soil sampling) on the excavated material where feasible. The intent is to leave unexcavated deposits for the future, where research will be guided by different questions and have access to potentially more refined technology and methods. As a result, the program has been limited to small test units, and moreover, a series of blocks of 2-by-2 meter units, excavated mostly in "checkerboard" pattern in the yard. Artifacts, samples, and records from the excavation are currently curated by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Departments of Architectural and Page 10 Archaeological Research, as well as the Collections, Conservation, and Museums division, in Williamsburg, Virginia.

The spatial organization of the archaeological project has relied on three primary historic illustrations of the garden's space prior to the photographs which become common in the mid-nineteenth century, each depicting a slightly different layout of the space. The most notable and earliest of these depictions is the "Bodleian Plate" of 1740, discovered in the Bodleian Library at Oxford in 1929. This engraving proved to be instrumental in the 1930s restoration of not only the Wren Building, but also the reconstruction of the Governor's Palace and the Capitol building by Colonial Williamsburg.

Figure 1. Bodleian Plate, Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK

Figure 1. Bodleian Plate, Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK

Two much later maps, the only other eighteenth-century sources to show the gardens in any detail, are the "Simcoe" map of 1781 (Martin, 1991) and the Desandroüins map of 1782. The Desandroüins map appears to show six spatial divisions in the yard, all half-fenced on the north side, a decidedly unusual layout. Desandroüins map also indicates that the beds may be slightly offset rather than perfectly aligned.

Page 11 Figure 2. Detail of Desandroüins Map (1781)

Figure 2. Detail of Desandroüins Map (1781)

The Simcoe Map, contemporary with the Desandroüins map, shows an altogether different layout of the yard space, one that is somewhat more in accordance with the Bodleian plate, featuring two large divisions, one north and one south of the central axis.

Figure 3. Detail of Simcoe Map (1782)

Figure 3. Detail of Simcoe Map (1782)

None of the other early depictions of the College, such as the 1702 Franz Ludwig Michel drawing of the east elevation (Kornwolf, 1989, p. 42) shows elements of the formal landscape around the building.

Page 12 Figure 4. College Building 1702, Franz Ludwig Michel, Bergerbibliothek, Bern, Switzerland

Figure 4. College Building 1702, Franz Ludwig Michel, Bergerbibliothek, Bern, Switzerland

The 2004-2007 archaeological work in the Wren Yard accomplished what was intended: finding evidence of the late seventeenth- early eighteenth-century formal garden on the east side of the College Building as depicted on the Bodleian Plate and recorded in historical documents. Although the geophysical survey conducted by Bruce Bevan and the first (2005) season of excavation produced no features relating to the garden, they certainly added to the record of activities that took place in the Wren Yard after the garden was long-since replaced by a tree park. Significant in the 2006 field season, however, was the discovery of three planting holes at the lowest stratigraphic level. Although compromised by later activities, the holes are consistent in size for small topiaries as those depicted on the Plate; they are spaced exactly nine feet apart and are aligned with the Wren Building, not with the town grid. The next season of field school excavation located part of what appears to be a ditch along the central path and plantings suspected to be part of the hedgerow shown in the 1740 Bodleian Plate. Late in the last season, two post holes along the hedgerow plantings were interpreted as a garden gate, meaningfully located along an axis if drawn between the southwest corner of the President's House and the northwest corner of the Brafferton. If this gate is a part of the original garden plan, it dates to after the 1732 construction of the President's House.

The archaeology of the Wren Yard was much more than an endeavor to find physical evidence of a historical feature; it was a significant learning Page 13 experience for the students that took part in both the excavation and the documentary and scientific research surrounding the project.

Acknowledgements

The Wren Garden Project was possible by a generous gift from Suzann Wilson Matthews '71. It was supported by the efforts, enthusiasm and contributions of time and money of many individuals, both at the College and Colonial Williamsburg. The largest efforts were those of the Anthropology Field School students who braved the heat and biting insects to unearth and record the physical evidence of the Wren Yard Garden.

From the College of William & Mary:

- Louise Lambert Kale, Director of the Historic Campus

- Ben Skolnik

- Billy Coyle

- Ben Pryor

From the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation:

- Marley R. Brown III, Director, Archaeological Research

- Lucie Vinciguerra completed the graphics for this report

- Jason Boroughs

- Dessa Lightfoot

- Nadejda Coonan

- Tony Herrmann

- Kelly Ladd-Kostro

- Jim Bowers

- Joanne Bowen

- Robert "Buddy" Paulett

- Steve Atkins

- Susan Christie

- Andrew Edwards

- Hans Schwartz formatted this report

Chapter 2

Historical Background

Martha C. McCartney

Research Strategy

Archival research was undertaken in support of archaeological investigations in the courtyard of the College of William and Mary's Wren Building. Research initially focused upon the examination of historical maps on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Rockefeller Library, the Library of Virginia, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, the Virginia Historical Society, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives. Use was made of bibliographical indices of Virginia maps. Maps reproduced in the Official Atlas of the Civil War, the American Campaigns of Rochambeau's Army, and Virginia in Maps were examined.

Research was carried out in published and unpublished sources that are on file at the College of William and Mary's Swem Library and at the Rockefeller Library. Background data on the development of the college and its campus were extracted from the Swem Index; the Virginia Gazette index; J. E. Morpurgo's book, Their Majesties' Royall College: William and Mary Colledge in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries; Wilford Kale's Hark Upon the Gale; Dr. James D. Kornwolf's work, So Good a Design, The Colonial Campus of the College of William and Mary: Its History, Background and Legacy; Parke Rouse's Cows on the Campus and his A House for a President: 250 Years on the Campus of the College of William and Mary; and John W. Reps' Tidewater Towns: City Planning in Colonial Virginia and Maryland. The works of Hugh Jones, William Byrd II of Westover, and others were utilized as were the works of Peter Martin and other garden historians.

Extensive use was made of research reports and data compiled by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation staff members. Due to the college's traditional link with the Virginia government, extensive research also was carried out in official records generated by the legislature and the governor's council. Use was made of eighteenth century issues of the Virginia Gazette, where information was found on gardening activities at the college. The garden journal kept by Joseph Hornsby, an avid horticulturist, was examined, as were garden journals kept by John Custis and others.

Because the Civilian Conservation Corps was known to have undertaken projects on the college's property, efforts were made to collect data on the Page 16 C.C.C.'s activities in the Williamsburg area and to learn whether C.C.C. workers ever undertook projects on the historic campus. Research was conducted at the Swem Library and the Daily Press Library in Newport News. John A. Salmond's The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study provided general background information on the C.C.C. Research was carried out in William and Mary's Buildings and Grounds map archives, where early site plans and plats of the College's campus and outlying properties are on file. The architectural files of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation were searched. It was determined that data on specific C.C.C. units are on file at the Federal Record Center in Reston, Virginia.

Data Limitations

Despite the significance of the College of William and Mary as a historic property and educational institution, very little information has been compiled on the evolution of its campus. The late E. G. Swem, who extracted a considerable amount of information from surviving fragments of the Board of Visitors' minutes, and James D. Kornwolf, who utilized a relatively broad variety of primary resources, provided useful background on the college's history and the campus's older buildings. Wilford Kale, whose photo-documentary history of the college includes pictures of the campus during the late nineteenth and early-to-mid-twentieth centuries, provided much helpful information.

Thanks to the fact that the college was occupied by military personnel during the American Revolution, detailed maps were produced by wartime cartographers. These maps were extremely helpful in determining land use patterns within the study area. Civil War cartographers' maps provide little useful information but military accounts shed light upon how the campus was used. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, several artists produced sketches and paintings of the college, focusing their attention upon the old campus.

Historical Overview

The Seventeenth Century

In 1693 the College of William and Mary was chartered by King William and Queen Mary, who endowed the newly-created educational institution with 20,000 acres of land. The monarchs also contributed public revenues (such as duties upon exported skins, furs tobacco, and imported liquors) toward its construction and support. The college, whose faculty was to consist of a president and six masters or professors, was to have a grammar school, a philosophical school, and a divinity school. One of the main goals in Page 17 establishing the college was to educate clergymen, who were then in short supply in the colony (Hartwell et al. 1964:69-70; Beverley 1947:265).

The main building of the College of William and Mary was constructed upon 330 acres that were purchased from Thomas Ballard on December 20, 1693, land that lay to the west of "the church now standing in Middle Plantation old fields." The property extended to Archer's Hope Swamp (at the head of College Creek) and straddled the forerunners of Richmond and Jamestown Roads. A plat that was made for Thomas Ludwell in 1678 defines the boundaries of the tract at the time it was conveyed to Thomas Ballard. In 1694 the college property's boundary stones were set out, two of which still survive (Kale 1985:20; Kornwolf 1989:35-36, 67).

Some scholars believe that the college's central building and gardens were designed in England by the Office of Public Works, with the assistance of Christopher Wren. By 1694 a grammar school was opened "in a little School-House" close to the site where the main building was to be erected. In August 1695 the first bricks were laid for what eventually became known as the Wren Building. Construction proceeded haltingly during 1696 and 1697 (Beverley 1947:265-266; Hartwell et al. 1964:69-70; Kornwolf 1989:33-37).

From the beginning, there was concern that the college being built would be properly landscaped. In May 1694 John Evelyn sent a letter to John Walker, discussing the matter. He indicated that George London, the king's gardener, had sent "an ingenious servant of his" named James Road to Virginia. Road was supposed "to make and plant the Garden, designed for the new Colledge, newly built in yr Country; & likewise enquire out, what plants, rare in this Kingdome, may be transported thither." Thus, he apparently went to Virginia with plans for the gardens designed for the new college. When Roads returned to England, he was supposed to bring American plant specimens that he collected. Scholars have noted that James Road's master, George London, was responsible for the landscape design at Hampton Court, a Tudor palace that was being improved under the direction of Sir Christopher Wren (Godson et al. I:30, 34, 75; Bourne 1970:27).

In 1697 the grammar school reportedly was "in a thriving way" and the main college building was said to be "carry'd up one Half of the design'd Quadrangle" (Hartwell et al. 1964:71). Theodorick Bland's 1699 drawing of Williamsburg and Princess Anne's and Queen Mary's Ports indicates that the Wren Building was then L-shaped. Bland's rendering indicates that only the north and east sides of the structure were complete. A student in May 1699 made reference to the college's kitchen, buttery, gardens, and woods. By midyear the Wren Building also was ready for use (Reps 1972:142, 150; Tyler 1907:129; Bullock 1961:45; Beverley 1947:97-100; Swem 1928:218).

The Eighteenth Century

Page 18In April 1700, when Virginia's capital was shifted from Jamestown to Williamsburg, the college building was used as the colony's statehouse. In 1705, only a year after government officials had vacated the premises, the Wren Building was destroyed by fire. Efforts were made to rebuild it and by 1716 construction was complete. In 1723 the Indian school, whose student body was small, moved into the newly erected Brafferton building (Kornwolf 1989:37; Bullock 1961:45-48; Swem 1928:218). A year later, Hugh Jones wrote that the piazza of the main college building was "approached by a good Walk, and a Grand Entrance by steps, with good Courts and Gardens about it" and that there was "a good House and Apartments for the Indian Master and his Scholars, and Out-Houses and a large Pasture enclosed like a Park with about 150 acres of Land adjoining, for occasional Uses." This statement suggests strongly that the gardens were on the west side of the Wren Building, where the piazza is located. It is probable that most of the plantings were utilitarian in nature: kitchen or vegetable gardens. No references pertaining to landscape features on the east side of the Wren Building have been found predating Robert Carter's September 11, 1727, comment about a proclamation's being given "at the Capitol, in the Marketplace, [and] on the Colledge green." He said that the herald was on horseback and that "ye Gov'r & myself [were] in the first coach" (Carter, September 11, 1727). The reference to the college green suggests that there was an expanse of grass on the east side of the Wren Building (Jones 1956:66-67; Kornwolf 1989:34, 37; Bullock 1961:45-48; Swem 1928:218; Godson et al. I:75-76).

However, during Governor William Gooch's administration, some landscape improvements may have been made. A February 1729 document, quoted in an 1874 history of the college, made reference to its main building's being "adorned with a handsome garden … [laid out] all in courts, gardens, and orchards." The writer, however, failed to specify where these landscape features were (Martin 1984:41). It is probable that construction of the Brafferton and the President's House brought attention to the east side of the Wren Building and its frontage on Duke of Gloucester Street.

On July 31, 1732, William Dawson, informed the Bishop of London that:

The foundations of a common brick House for the President was laid opposite to Brafferton. It is to be finished for £650 current money by October 1733, according to the articles of agreement. These two buildings will appear at a small distance from the East front of the College, before which is a Garden planted with Ever-Greens kept in very good Order. The Hall and Chapel, joining to the west Front towards the Kitchen Garden, form two handsome wings [Tyler 1900-1901:220].The Rev. Dawson's description sheds some light upon the types of plants that may have been present. It also tends to coincide with the image depicted on the Bodleian Plate, which suggests that on the east side of the Wren Building, Page 19 and flanked by the Brafferton and the President's House, was a formal planting of clipped shrubbery framed pathways and plots of grass. Absent were large trees.

In 1727, a set of statutes were formulated that governed the mission and management of the College of William and Mary. They were updated 1736, and again in 1758. While most of those statutes deal with the college's curriculum and the institution's hierarchy, one, which is entitled "Of the ordinary Government of the College," addresses practical matters, such as the personnel essential to maintenance and conducting day-to-day operations. Oversight was entrusted to the President and Six Masters: two professors of divinity, two professors of philosophy, the master of the Grammar School, and the master of the Indian School. Besides the need for an Usher in the Grammar School, a Bursar, and a Library-keeper, the college was to employ a janitor, a cook, a butler, workmen "for building or repairing," and a gardener. An addendum noted that "the President and Masters take Care to provide proper Quantities of Wheat and Corn, at such Seasons when they may be purchased upon the easiest Terms" so that "only one Sort of Bread may be used for the Masters and Scholars" (Goodwin 1970:Appendix II [from WMQ 16 (ser 1:241-256] 250-251, 256).

In accord with these statutes, the College of William and Mary's board of visitors commenced hiring gardeners, men who would have performed their duties with the assistance of slave labor. One of the tasks for which the college gardener was responsible would have been the production of food crops. In 1727 the Governor's Council authorized payment to Thomas Crease, who had served as palace gardener during Governor Hugh Drysdale's administration, "for his Service and labourers in assisting in putting in order the Gardens belonging to the Governor's house." Crease became the college's gardener around 1726 and held that position until at least January 1738. York County records dating to 1725 indicate that he was a gardener, a married man, and owned a half-acre lot in the city (Martin 1991:40-41).1

An advertisement that appeared in the January 13, 1738, edition of the Virginia Gazette reveals that college gardener Thomas Crease sold seeds and plant materials. He published a notice that:

GENTLEMEN and others, may be supply'd with good Garden Pease, Beans, and several other Sorts of Garden Seeds. Also, with great Choice of Flower Roots; likewise Trees of several Sorts and Sizes, fit to plant, as Ornamentals in Gentlemen's Gardens, at very reasonable Rates [Parks, January 13, 1738].Page 20 It is unclear whether Crease was propagating some of the plant materials he sold or obtaining all of them from outside sources. However, the seeds sold by Crease's successors at the college were imported, raising the possibility that his were, too.

Throughout much of the eighteenth century the college was supported by tax revenues, private endowments, royal warrants, and income from its dower lands. In 1747, when the colony's statehouse burned, the Virginia Assembly again convened in the Wren Building. Throughout the eighteenth century, the college played a significant role in the social and economic life of Williamsburg and the colony (Morpurgo 1976:88; Kornwolf 1989:46; Reps 1972:176; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 1985:II:1-12).

On January 28, 1773, the Virginia Gazette, published by Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, announced the death of Mr. James Nicholson, the college gardener. The decedent had served "for many years as steward and gardener" and had performed his duties "with much satisfaction to all concerned." The author of Nicholson's obituary stated that "His Labour of almost 30 years, after much raking and scraping" had resulted in his saving a handsome sum, which he had bequeathed "to his Relations in Scotland" (Purdie and Dixon, January 28, 1773) .

The Virginia Gazette, published by Clementina Rind, also carried Nicholson's obituary. It stated that:

On Friday last departed this life, in a good old age, at William and Mary college, Mr. JAMES NICOLSON, who for upwards of twenty years discharged, with the most unshaken fidelity, the many important trusts that were reposed in him by the professors of that seminary. The warm zeal, and sincere regard, for the interest of the college, which animated all his proceedings, will ever render his memory sacred to every friend of it. The genuine humility of his soul was invariably indicated by that regularity of action, and independence of sentiment, which were the shining characteristics of his venerable conduct. By his indefatigable industry, and a moderate frugality, he was enabled to leave some mementos to friends and relations of his esteem and affection for them; and to all that knew him, the noble example of an honest man, and a good Christian [Rind, January 28, 1773).Thus, the late James Nicholson served as the College of William and Mary's gardener for between 20 and 30 years. On February 18, 1773, Robert Nicholson, the gardener's executor, asks all creditors and debtors to the decedent's estate to notify him. He also announced that he had "for sale a Quantity of Garden seeds" (Dixon, February 18, 1773) . Page 21

James Wilson succeeded James Nicholson as gardener at the College of William and Mary. He, like Thomas Crease in 1738, and James Nicholson's executor in 1773, advertised that he had seeds for sale. Wilson's announcement suggests that the college gardens produced a broad variety of vegetables for table use. On March 3, 1774, an announcement in the Virginia Gazette proclaimed:

Just Imported, and to be SOLD by James Wilson, Gardener at the College, the following SEEDS. which are all fresh and the best of their Kinds. PEASE: Earliest, best Charlton, Golden Hotspur, Nonpareil, Marrowfat, Green Rouncival, Spanish Moratto, and Glory of England. BEANS: Mazagon, Long Pod, Windsor, Early Hotspur, and White Blossom. Cabbage: Early Yorkshire, Early Battersea, Early Sugar Loaf, White Dutch, Red, and large Hollow. Turnip: Early Dutch, Norfolk, Early Green and Red Round. Radish: Salmon, Short Topped, White Spinach, and Black. Green and Yellow Savoy, White and Purple Broccoli, Early and Late Cauliflower, Red and White Beet, White Mustard, Round Leaf and Common Cresses, Solid Celery, London Leek, Early Carrot, Skirret, Lettuce seed of all sorts, fine Spinage Seed, Cucumber seeds of different kinds, and a great variety of other seeds too tedious to mention [Purdie and Dixon, March 3, 1774].During this period the college continued to have a pasture, where livestock could graze. In September 1774 someone stole a horse from the college's pasture (Purdie and Dixon, September 8, 1774).

At the onset of the American Revolution, an estimated 70 students were enrolled at the College of William and Mary. During the war, classes continued to be held despite the fact that many members of both the faculty and the student body joined military units. In 1775 Colonel Patrick Henry established a military encampment on the grounds of the college, where Virginia troops assembled and trained. Historical maps suggest that much of this activity occurred on the east side of the Wren Building. Later in the war, the President's House was used as a hospital for wounded French soldiers, at which time it was destroyed by fire (Kale 1985:52, 57-59). Undoubtedly all of these activities would have taken a toll upon any landscape features that were present. A 1777 announcement about a stolen horse states that it was taken from the "college gate" (Purdie, March 14, 1777, supplement).

On May 31, 1777, Ebenezer Hazard, who visited Williamsburg, commented that the town's principal buildings were the college, the public hospital, the governor's palace, and the capitol. He said that the college was "badly contrived, and the Inside of it is shabby; it is 2½ Stories high, has Wings & dormer Windows. He added that "At each End of the East Front is a two Story brick House, one for the President, the other is for an Indian School." He noted that "At this Front of the College is a large Court Yard, ornamented with Gravel Walks, Trees cut into different Forms, & Grass." He stated that on the Page 22 west was "a Court Yard and a large Kitchen Garden" (Shelley 1954:405). Historian Peter Martin noted that the Bodleian Plate and Ebenezer Hazard's comments indicate that the acreage on the east side of the Wren Building was symmetrical and formal, a design suitable for a public building. Martin stated that the orderliness and grace this view presented was "an emblem of what the college stood for in the New World. Martin also noted that "Archaeological investigations in the 1930s proved the Bodleian Plate's depiction of the Palace gardens to be correct in outline and shape, so there is every reason to trust what it shows of the college gardens" (Godson et al. 1993:1:76; Martin 1991:41) .

Late in 1779, when the college was experiencing serious financial problems, an attempt was made to make it self-supporting. On December 18, 1779, college officials placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette, offering for rent the kitchen and gardens. The public notice also offered for hire the slaves who worked in the kitchen and garden (Dixon, December 18, 1779). Undoubtedly, loss of the slaves who maintained the garden would have precipitated a decline in its condition.

In 1781-1782, several French cartographers prepared maps of Williamsburg, depicting the sites at which many of the town's buildings were located. Rochambeau's senior engineer, Colonel Jean-Nicholas Desandroüins, whose signed watercolor rendering of Williamsburg was particularly sensitive, indicate that large and relatively elaborate gardens were present on the west side of the Wren Building. He indicated that the study area, defined by the Wren Building, the Brafferton, and the President's House, contained three pairs of planting beds that seemed to have been enclosed. Desandroüins arrived in Virginia in September 1781 on the eve of the Yorktown Campaign. In early October he had what he described as a "cruel accident," perhaps an injury or illness, while he was in Williamsburg. Although he was unable to participate in the siege of Yorktown, in 1782 he asked for a promotion on account of the services he had performed, which he deemed essential to the army's success. In December 1782 Desandroüins and the troops from the Bourbonnaise Regiment set sail from Boston (McCartney 1999-2000:46-47). Jean-Nicholas Desandroüins' dates of arrival and departure indicate that his detailed map of Williamsburg was prepared between September 1781 and December 1782.

Page 23 Figure 5. Detail of St. Simone Map (1781)

Figure 5. Detail of St. Simone Map (1781)

Figure 6. Detail of Berthier Map (1782)

Figure 6. Detail of Berthier Map (1782)

The maps prepared by St. Simone (1781a) and Berthier (1781a, 1781b) confirm Desandroüins' interpretation. Other military mapmakers identified the college and indicated that its campus was occupied by the Allied Army, but they failed to portray the layout of its landscape setting (St. Simone 1781b; Chesnoy 1781; Chantavoine 1781). John Simcoe's map (1781-1782) suggests that the gardens on the east side of the Wren Building were symmetrical; however he depicted a simpler design than Desandroüins had suggested. The anonymous Frenchman who prepared a detailed map of Williamsburg in 1782 and identified some of the buildings on the campus of the College of William and Mary failed to provide information on the study area (Anonymous 1782).

After the close of the American Revolution, the College of William and Mary entered a period of decline, for its official connection with the British monarchy was severed and no support was forthcoming from the newly-organized Commonwealth of Virginia. In 1787 the college was largely divested of its public funds and real estate comprised its primary source of revenue. The size of the college's student body dwindled as Tidewater Virginia's population declined. Also, a new university was established in Charlottesville.

The Nineteenth Century

Although only 17 students were enrolled at the College of William and Mary in 1833-1834, by 1839-1840 that number had increased significantly. On February 8, 1859, a fire at the college severely damaged the Wren Building. However, it was quickly repaired and restored to use (Reps 1972:191; Swem 1928:292).

Much damage was inflicted upon the college and its campus during the Civil War. On the eve of the Battle of Williamsburg, Confederate troops reportedly used as firewood many of the wooden fences that enclosed the Page 24 college's grounds. During the Peninsular Campaign, when Williamsburg fell under the control of the Union Army, the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry occupied the town. During that period, the Brafferton was used as the office and quarters of the military officer in command of the town, the Wren Building became a depot of commissary stores, and the President's house and Brafferton sustained considerable damage (Swem 1928:218, 292; Kale 1985:87).

A map prepared by A. A. Humphreys (1862) reveals that a primitive roadway then extended into the woods to the northwest of the college (Gilmer 1863, 1864). On September 9, 1862, a detachment of Confederate soldiers made a surprise raid upon Williamsburg, briefly routing their adversaries. Later in the day, after the Union Army regained control, some of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry's men (who were intoxicated) set fire to the Wren Building (Swem 1928:292).

In 1865 attempts were made to revive the College of William and Mary as an educational institution. The United States government contributed toward the reconstruction of the Wren Building, since it had been destroyed by the unauthorized actions of Federal troops. Although the structure was rebuilt upon its former site, the college faltered and then failed in its struggled to survive. By 1881 the institution was forced to close due to lack of funds. In 1888, however, the College of William and Mary again opened its doors to students, thanks largely to the efforts of Lyon G. Tyler, who succeeded in restructuring, modernizing, and expanding the college's curriculum. Enrollment grew steadily and in 1889 the college had 104 students and seven professors. In 1906 William and Mary became a state-sponsored educational institution, a transition that significantly strengthened its financial position (Swem 1928:218; Rouse 1973:101).

The earliest photographs that depict the WESTERN part of the campus date to the 1890s, and reveal that it was then devoid of buildings (Kale 1985:103). In 1904 when a topographic quadrangle sheet was prepared that included Williamsburg, the Wren Building and three other structures were shown on the campus of the college (USGS 1904). In 1919, when Dr. Julian A. C. Chandler became president of the College of William and Mary, he set about strengthening its curriculum and constructing a number of new buildings. It was likely during that period that the college's campus was expanded. During the 1920s Jefferson, Monroe, Trinkle, Rogers (Chancellor's), Barrett, Old Dominion, Phi Beta Kappa (that is, the original structure of that name) and Washington Halls were built, along with the Blow Gymnasium and the dwellings that comprise Sorority Court. During the 1930s, Marshall-Wythe, the King Infirmary (later renamed Hunt Hall) and Brown and Chandler halls were constructed. In 1935 the Sunken Garden was built, as was Cary Stadium, which was named for T. Archibald Cary (Kale 1985:122-124, 132, 148-151, 167-168; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Architectural Vertical Files).

Page 25It was during the mid-1930s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was active throughout the United States that the men of the CCC came to the Williamsburg area where they were employed in a variety of public works projects that were under the auspices of the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) program. The CCC and associated groups were part of a Depression-era governmental experiment that combined social welfare with conservation work, part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. The CCC went out of business when the United States entered World War II. During the nine years that the CCC was in existence, an estimated 2,500,000 young men participated in its programs. Not only were numerous public works projects completed and CCC workers trained in useful skills, the families of CCC enrollees received monthly allotment checks that enabled them to sustain themselves during the Depression (Salmond 1967:1-12).

In spring 1933 CCC workers' camps were established in the Williamsburg and Yorktown areas. One of their first tasks was repairing some of the damage done in the 1932 hurricane. During the time that CCC workers were employed in the Williamsburg area, they conducted archaeological excavations at Jamestown and built what was called the Lake Matoaka State Park on the campus of the College of William and Mary. These men, who were employed under the ECW program, worked at the direction of the Department of the Interior but were under the supervision and management of the army. The CCC installation in Williamsburg was Camp Company No. 2303 (Camp EM-5) (Daily Press, December 17, 1990).

Chapter 3

Previous Archaeology

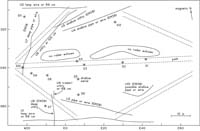

Most of the previous archaeology of the Wren Yard has focused on the building itself, notably Prentice Duell's 1932 report documenting the four forms of the Wren Building. Colonial Williamsburg's files also have annotated maps by James M. Knight, noting locations of trenching around the north, south, and west sides of the Wren Building in 1931, including the location of brick clamp remains on the south side of the main college building and a brick-lined well to its northeast. Knight also excavated four widely-spaced north-south trenches (as opposed to his then-standard diagonal trenches) through the east yard in 1950 and 1953. The 1950 trenching revealed brick footings that corresponded to the plan of an unfinished addition designed by Thomas Jefferson in 1772. Very little was discovered in the 1953 trenching; Knight's annotations on the map include brief descriptions of layers of brick atop marl (very near 2005 Test Unit 1), a few ash deposits, and packed marl and slate inclusions near the radar anomaly Bevan located in 2004 in front of the Brafferton. Knight's methods, however, were ill-suited to detecting subtle features in subsoil such as planting beds or postholes. Prior to 2004, Knight's excavations remain the most recent archaeological attempt at examining the east yard.

Further work in the historic campus has been relegated to areas outside the present study area. Colonial Williamsburg archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume conducted the first stratigraphic excavation at the College when he examined the basement of the President's House in 1972, finding evidence of the brick drainage system that likely relates to what was later discovered during monitoring activities in 2006, and potentially a very ambiguous feature found in the 2005 block excavations (discussed as "Drainage Feature/Brick Crumb in Chapter 5).

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a series of compliance surveys documented various additional archaeological resources within the historic campus. In 1975, archaeologists from Virginia Research Center for Archaeology (VRCA) recorded another portion of the Jefferson addition to the Wren Building that was exposed in a utility trench (Kale 1977 in Moore and Miller 2010:9). In 1980 the VRCA also monitored the excavation of trenches for air conditioning service into the President's House, yielding fragments of stoneware, Chinese and European porcelain, tin-enameled earthenware, creamware, glass and metal, all dating from the 1730s to the late 1800s (Rouse 1983:47, 218). In 1997, Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research tested the area north of the Wren Building and west of Page 28 the President's Guest House that resulted in the discovery of a possible Middle Plantation-era foundation (Muraca 1997). Two years later, however, a more substantive investigation by the William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research (WMCAR) revealed the foundation likely dates to the early nineteenth century rather than seventeenth century (Higgins and Underwood 2001). WMCAR also documented the various uses of the yard areas north and south of the Wren Building over three centuries. Their investigation recovered thousands of artifacts and revealed dozens of features, including evidence of the yard's cultivation prior to the Wren Building's construction as well as a long-maintained service yard fence line (Higgins and Underwood 2001). WMCAR also excavated a portion of the President's House Parking Lot in advance of utility upgrades in 2006. This investigation revealed the remains of at least four structures and twenty features (Moore 2006). Also in 2006, archaeological monitors from Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research recorded an eighteenth-century brick drain west of the President's House as well as a previously undocumented well shaft in the north yard of the Wren Building (Archer and Vinciguerra 2006) (Kostro 2013:23).

All of the testing prior to the current project is depicted in Figure 7, and available only in the printed report as an accompanying large-scale map, "Wren Yard Garden, Previous Archaeology, All Explorations Prior to 2005."

Page 29 Figure 7. Wren Yard Garden, Previous Archaeology, All Explorations Prior to 2005

Figure 7. Wren Yard Garden, Previous Archaeology, All Explorations Prior to 2005

Figure 8. Detail of Previous Archaeological findings in the region of the President's House.

Figure 8. Detail of Previous Archaeological findings in the region of the President's House.

Figure 9. Detail of Previous Archaeology to the West and South of the Wren Building

Figure 9. Detail of Previous Archaeology to the West and South of the Wren Building

Chapter 4

Field and Laboratory Procedures

A grid was established just south of the President's House for the summer 2005 block excavation. A permanent datum point ("Station 1"), was selected. This was the southwest corner of the storm drain grate immediately in front of the President's House, a feature unlikely to be altered in the near future. This point was given the arbitrary grid coordinate point of 500 North/500 East, to eliminate the untidy practice of needing negative grid numbers depending on how the excavation would eventually expand.

The excavation block was designed as a "checkerboard" pattern of 2m x 2m units. While one-meter square units afford better spatial control over artifacts and sampling, and are commonly used on domestic sites, such smaller units were impractical for the large garden features expected (cf. Yentsch and Kratzer 1994). It was hoped the larger sized excavation units would provide a better understanding of any features in the subsoil. The checkerboard pattern allows not only a greater physical area to be examined for any features that may connect through the unexcavated portions of the "checkerboard", but at the same time preserves half of the overall excavation block area as untouched, in-situ deposit for any future research.

The block was primarily intended to view a north-south path, and also expanded slightly east and west. The rationale for the excavation block design was to first get a linear transect across the yard between the President's House and the central walkway. All depictions of the formal garden show bilateral symmetry between the north and south halves of the yard. If any evidence for the colonial garden was found in the northern portion of the yard, there would presumably be a mirror image of the same features in the unexcavated south half of the yard, assuming the disturbance and post-depositional modifications of the yard were similar in both halves. Therefore, the north-south excavation transect was not planned to cross the central walkway, but rather expand with units east and west of the central axis.

All contexts found within a 2 by 2-meter unit would receive a discrete number. Features such as post holes, that require unique numbers for their act of creation would receive "cut" numbers. The Harris Matrix system of stratigraphic control was used to "phase" the various features and strata into their respective temporal contexts. Each context would require the completion of a Context Record Sheet, and example of which is shown in Figure 10. The paper record was entered into The Museum System database, and then stored Page 34 in the Documentation Room at the Archaeological Collections Building (ACB) for safe-keeping.

Contexts and features deemed significant were drawn to scale using standard 10 by 10 to the centimeter metric graph paper, and a drawing frame. All elevations and some features and interfaces between strata would be recorded using the total station and data logger. Both forms of data collection are brought in to AutoCad design software to create the site's graphic record.

Artifacts recovered from each context were bagged in plastic zipper bags upon which were written the unique context number, grid coordinates, description, date, and initials of the excavator and, if appropriate, screener. When a context was completed, the artifact bag received an "F" (finished) mark and was transferred to the ACB for processing and curation.

Sampling and Excavation Procedures

Each two-meter square was excavated as a single unit, with no attempt to maintain general spatial control over the artifacts from layers other than the two-meter grid coordinates. Features were all mapped precisely to the grid using a laser theodolite/total station.

Excavation proceeded stratigraphically, using "natural" visual and textural changes in deposit composition to indicate a context change as opposed to arbitrary levels of a given thickness (e.g., 10 centimeter levels). Closing elevations of each stratigraphic level were taken with the transit to permit accurate 3-D mapping of the layers.

Features were also excavated stratigraphically, each feature being assigned a "cut" and "fill" number in accordance with the Harris Matrix system of recording (Harris, 1979). Each context was assigned a number in accordance with Colonial Williamsburg's recording system, consisting of a block/area designation, plus an individual context number. "16GA-00001" therefore consists of Block 16 (the historic college campus on CWF's base map), excavation area GA (the garden excavation project), and a sequential context number. Artifacts from each context are later catalogued by a two-letter extension indicating an individual artifact from a specified context "16GA- 00001-AA" is then the first coded artifact from context 16GA-00001 (a creamware fragment, in this case, from the topsoil of Test Unit 1).

Upon completed excavation of each unit, at least one profile drawing was made, further documenting the stratigraphic interfaces and the vertical composition of each unit. For features, both plan and profile drawings were Page 35 made prior to and during excavation. Features were generally bisected and profiled, followed by the excavation of the remaining portion of the feature.

Laboratory Methods

Material produced by archaeological excavation consists of several different types. Artifacts are generally either ceramic, glass, metal, or on rare occasions, organic. Faunal material is animal bone or shellfish shell, and environmental material is generally archaeobotanical in nature. All of these materials were recovered from sites and are remaindered to the ACB laboratory. Artifacts are cleaned and sorted into material type and then catalogued into a database program, currently The Museum System (TMS). Artifacts requiring conservation are sent to the Collections Building on the Bruton Heights Campus for conservation and stabilization. Contexts deemed significant by the site archaeologist will be retained for analysis and crossmending.

Faunal material (bone) was removed from the artifact lab after cleaning and sent to the faunal/environmental lab for identification and analysis. Botanical materials such as phytoliths and pollen are retained in the faunal/environmental lab for later analysis by outside consultants. Large (5- 10 liter) bags of soil collected from certain contexts by the archaeologist for the express purpose of flotation will be processed by the environmental lab using a Flote-Tech flotation machine. The "heavy" fractions were picked for seeds, small bones, and tiny artifacts, and a subset of the light fractions were analyzed as part of the student projects undertaken as part of this project.

Page 36Chapter 5

Excavation Description and Results

The archaeological work in the Wren Yard took place over several years and included geophysical testing, two exploratory test unit projects in 2005, three block excavations in 2005 through 2007, and additional testing in 2007 in order to explore what was believed to be a garden gate. This work is discussed below:

2004-2005 Testing Strategies2

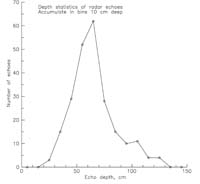

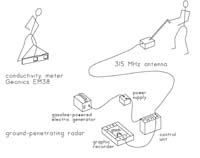

Geophysical Survey

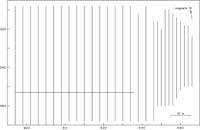

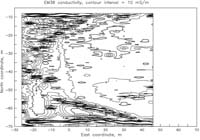

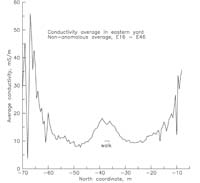

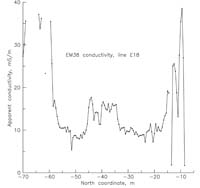

Figure 11. Composite Geophysical Drawing

Figure 11. Composite Geophysical Drawing

In September of 2004, geophysicist Bruce Bevan conducted a non-invasive survey of the College Yard using ground penetrating radar and conductivity instruments (Appendix 3). This assessment was intended to determine locations of potential anomalies that might indicate relict garden features or potential fruitful areas for archaeological excavation. Bevan's report noted several unusual anomalies, including indications that the central east-west walkway of the College yard was likely wider than its current configuration. Also, radar echoes indicated some type of flat, prepared surface approximately 20 meters north of Brafferton Hall, at approximately 40 centimeters below the surface. During the 2006 field season, a one-by-one meter excavation square (458N/503E) was placed over this anomaly but no unusual surface or deposit was found.

Overall, the geophysical evidence did not characterize any regular geometric patterning of anomalies that would be consistent with the garden layout as depicted on the Bodleian plate, or any of the other historic descriptions or depictions. Furthermore, Bevan notes that the survey also failed to distinguish known archaeological trenching in the yard from the James Knight excavations in the 1930s and 1950s. This suggests that the geophysical methods may be too limited in resolution to find discrete locations of soil disturbance such as garden beds, given the possibility that more permanent garden architecture in the yard such as borders or walkways were removed or heavily disturbed. However, one anomaly located by Bevan seems to be consistent with the Civil War era earthwork ditch that was identified in 2006 (see discussion in 2006 excavation season section)

Test Units

Figure 12. Test Unit and 2005 Block Unit locations

Figure 12. Test Unit and 2005 Block Unit locations

Three one meter by one meter test units were excavated in the College Yard in the spring of 2005. Following on the geophysical survey, the test units were excavated in an attempt to characterize the stratigraphy of the yard, obtain preliminary soil samples, and assess potential locations for the planned block excavation during the summer field school season. The testing locations were spaced widely across the yard, one close to the Wren Building in the northwestern portion of the yard (Test Unit 1), another in the southeastern area of the yard (Test Unit 2), and a third immediately south of the central walkway near the center of the yard (Test Unit 3). Students from Anthropology 150W, Approaches to Ethnobotany (Spring 2005), anthropology graduate student Nadejda Coonan, and Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeological Research volunteers assisted with the testing. Excavation methods were consistent with general practice of Colonial Williamsburg's standard procedures, including excavation in stratigraphic (rather than arbitrary) levels, ¼-inch screening of all deposits for artifacts, and metric standard measurements.

Test Unit 1

Test Unit (TU) 1 was the first indication of the complexity of the college yard. Amusingly, the first excavated topsoil context in search of clues regarding the structure and content of the colonial formal gardens yielded an (obviously modern) plastic gardening tag fragment clearly marked with the word "JUNIPER" (16GA-00001-AR). The remaining layers of TU 1 provided a more forthright sense of the challenges to come with the Wren excavations.

Figure 13. Test Unit 1 — North sidewall

Figure 13. Test Unit 1 — North sidewall

TU 1 could not be completely excavated to the subsoil level due to logistical constraints of needing to excavate and backfill the units the same day. Nonetheless, TU 1 revealed several layers of discrete fills beneath the topsoil context.

A dark layer immediately below the topsoil terminated in a thin clay cap, beneath which a loamy layer dense with artifacts appeared.

The artifacts in the fills (particularly 16GA-00004 and 16GA-00008, below the modern surface) were rich with primarily architectural debris (window glass, nails, brick, roofing slate, lime mortar, plaster) as well as domestic artifacts. Terminus Post Quem (TPQ) dates from the artifacts place the excavated deposits to no earlier than the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Because many, but not all, of the artifacts appear to have been burned, much of TU 1 may likely relate to re-deposited materials from the various destruction, rebuilding and restoration episodes of the Wren Building itself (Duell, 1932).

Approximately 45 centimeters of artifact-rich deposit were excavated in TU 1. Because daylight was being lost, the decision was made to simply use a Page 41 soil probe to determine the extent of remaining cultural deposit before subsoil was reached. The probe showed that at least another 15 centimeters of cultural deposit remained.

Test Unit 2

Figure 14. Test Unit 2 — North Sidewall

Figure 14. Test Unit 2 — North Sidewall

TU 2, however, in the southeast corner of the yard, appeared to be relatively straightforward and more typical of minimally altered landscapes. The stratigraphy seen in TU 2 indicated natural soil profile development of an A horizon atop a sandy loam B horizon/archaeological deposit that included a very scant amount of artifacts including small fragments of window and bottle glass, metal fragments (including lead casting waste) and a possible buckle fragment. A single piece of creamware ceramic produced a TPQ date of no earlier than 1762 for TU 2.

Upon review of the later evidence, however, it is unclear if TU 2 reached the natural base of excavation to sterile subsoil, or whether the very thick layer of re-deposited clay present throughout the eastern portion of the Wren yard was misidentified in the field in this initial testing as the natural subsoil.

Test Unit 3

Test Unit 3 was placed immediately south of the central east-west walkway in the approximate center of the college yard. The unit was placed here in part to "ground-truth" or physically examine the expanded walkway seen by Bevan's geophysical analysis.

Page 42 Figure 15. College Building c. 1856 (CWF)

Figure 15. College Building c. 1856 (CWF)

Less than 10 centimeters below the surface a modest layer of crushed shell was apparent in TU 3. Stratigraphically, this appears to be comparatively recent, and the presence of aluminum foil generated a TPQ date of no earlier than 1947 for this surface. The earliest known photograph of the Wren yard, dated 1856, shows a well-trodden but not bricked walkway leading to the original statue of Lord Botetourt and presumably westward toward the Wren Building. It is unclear from the photograph whether crushed shell or marl would have been a component of the nineteenth-century walkway. Other early twentieth-century photographs show somewhat different layouts for walkways than are presently seen in the Wren yard.

Below the shell deposit was again found the clay fill or cap layer now known to extend through most of the eastern half of the Wren yard. Below the cap was a rich loam layer again replete with artifacts, primarily architectural (shell plaster, brick, shell, slate roofing tiles) but also bottle glass, a bone button fragment, and an "Indian head" type U.S. one cent piece providing a clear TPQ date of 1903 for the lower excavated layer of TU 3.

Page 43 Figure 16. Test Unit 3 - North Sidewall

Figure 16. Test Unit 3 - North Sidewall

As with TU 1, the unit could not be completely excavated due to a combination of inclement weather and the need to backfill the test unit the same day it was excavated. Overall the stratigraphy of TU 3 seems to accord best with that seen in the general block excavation.

2005 Excavation Block

Figure 17. Completed 2005 Excavation Block (CWF)

Figure 17. Completed 2005 Excavation Block (CWF)

Methodology and Rationale for Location

Following the geophysical survey and the spring 2005 testing, it was decided that the best evidence of any relict garden features would likely be in the eastern portion of the College yard. Based on TU 1, as well as examining the distribution of known modern utilities, it appeared that the western portion of the yard, near the Wren building would be more extensively disturbed. Moreover, the archaeological evidence seen in TU 1, and presumably elsewhere in the western half of the yard, was more related to the Wren building itself, its destruction episodes and modification, as opposed to the formal garden landscape. In all probability, the traces of destruction and modification of the Wren building would obscure rather than elucidate evidence of gardening beds and parterres being sought.

A grid was established just south of the President's House for the summer 2005 block excavation. A permanent datum point ("Station 1"), was selected. This is the southwest corner of the storm drain grate immediately in front of the President's House, a feature unlikely to be altered in the near future. This point was given the arbitrary grid coordinate point of 500 Page 45 North/500 East, to eliminate the untidy practice of needing negative grid numbers depending on how the excavation would eventually expand.

The block was primarily intended to view a north-south path, and also expanded slightly east and west. The rationale for the excavation block design was to first get a linear transect across the yard between the President's House and the central walkway. All depictions of the formal garden show bilateral symmetry between the north and south halves of the yard. If any evidence for the colonial garden was found in the northern portion of the yard, there would presumably be a mirror image of the same features in the unexcavated south half of the yard, assuming the disturbance and post-depositional modifications of the yard were similar in both halves. Therefore, the north-south excavation transect was not planned to cross the central walkway, but rather expand with units east and west of the central axis.

Sampling and Excavation Procedures — 2005

Each two-meter square was excavated as a single unit, with no attempt to maintain general spatial control over the artifacts from layers other than the two-meter grid coordinates. Features were all mapped precisely to the grid using a laser theodolite/total station.

All deposits from the first half of the excavation season were screened through ¼- inch mesh. All artifacts aside from brick and oyster shell were saved and catalogued, with samples of brick and oyster retained from deposits overwhelmed by these artifact types. Once it had been established that the layers above and including the "orange clay fill" (see stratigraphic discussion below) were clearly twentieth-century, during the second half of the excavation season, those layers were no longer screened in the expansion units, resulting in a fifty-percent screened sample of the upper layers of fill. Deposits below the clay cap were all screened for all units.

Flotation samples were also taken for every unit and layer below the clay cap. A standardized 35 liter sample was taken from layers. Experience with regional samples at CWF's Department of Archaeological Research environmental archaeology labs indicates that a 35 liter sample is a good volumetric compromise between the generally macrobotanical-poor deposits in the Tidewater region and a manageable volume of soil to transport and process efficiently. Feature soils were either floated in their entirety where feasible or fifty-percent sampled in the case of excessively large features such as 16GA- 00155/00156. Flotation sampling is a high-resolution approach to deposits, recovering not only plant remains, but also all artifacts greater than 2mm in the heavy fraction component. These samples can serve as a cross-check against the data from field screening for artifact categories such as microfaunal Page 46 remains and other small materials (straight pins, beads) that may not be consistently recovered in hardware cloth screens.

Furthermore, additional small-volume analytical samples were taken from each sub-clay cap layer, and also from each feature. These samples are commonly referred to as "phyto/chems" as they generally are used for phytolith or soil chemistry analysis, although they also serve as an archive of the matrix of each deposit, that which is destroyed by the excavation process, and may also be used for additional types of characterization analysis.

Twentieth-Century Features

Tile and Brick Drains

The most commonly encountered and time-consuming twentieth century features to excavate were terra cotta tile drains. Three separate segments on different orientations were uncovered in the excavation block.

These features have commonly been encountered during excavations in Williamsburg's historic area and date to the 1930s era restoration of the town. They appear to have been an unsuccessful experiment with an inexpensive type of drain. Each "D" shaped tile is simply placed in the trench abutting another tile; no joining compound is placed between the individual tiles. On either side of the drain tiles are placed brick fragments, likely pulled from the restoration projects as the buildings were renovated. In each case, these tiles were found filled in with silt. They likely became clogged quite soon after their installation through rainwater percolation washing silt into the drains.

Two of the drain lines were of this type of construction, one oriented slightly off east-west, and another on northwest-southeast orientation. The east-west line was found in unit 498/508 and 496/510, while the northwest-southeast line extends almost directly through the center of 484/510, 486/512, and 490/516. This drain segment also had associated evidence of the trench excavation 'heaped" alongside the cut for the drain, in the form of a brick crumb trampled area along the northwest side of the drain cut, especially obvious in 486N/512E and 484N/510E (contexts 16GA-00090 and 16GA- 00120).

One drain segment, found in 484N/510E and oriented east-west, appears to be more recent than the others, revealing no brick "supports", and is constructed of a higher-quality, more burnished hexagonal terra-cotta tile as opposed to the "D"-shaped tiles. It cuts through the path of the long northwest-southeast oriented segment that extends through 484/510, 486/512, and 490/516.

Page 47 Figure 18. 2005 Excavation Block — 20th-Century Features

Figure 18. 2005 Excavation Block — 20th-Century Features

The historic campus has a long history of drainage problems and creative solutions for alleviation of the same. Both colonial and restoration-period drain segments have appeared frequently in recent excavations (Archer, 2006) as well as James M. Knight's excavations of the President's house property in the 1930s.

The tile drains are immediately capped by the orange clay fill layer. While cuts are discernible, indicating the drains were dug in, and not just placed on the surface and buried by the fill, it is clear they were installed contemporaneously with the landscaping/grading episode that presumably completed the restoration work being done to the President's House and/or the Wren Building by the Williamsburg Holding Corporation (later known as the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation).

Lead-Wrapped Electric Wire

One unwelcome modern feature appears to be a potentially still-active electrical wire that is part of the streetlamp network in the College yard. This cable runs directly into a large, partially decayed tree stump in 498N/512E. This tree (several candidates for the stump's former above-ground component can be seen in historic photos) may have supported lighting fixtures as are seen in other portions of the yard today. The presence of a potential live wire, which was left supported by a soil pedestal and the stump disturbance in 498N/512E precluded much visibility of the subsoil/any potential colonial features in this unit. A small portion of 498N/508E is also intersected by the wire, in the south wall of the excavation.

Burnt Fill Deposit

Figure 19. Student Brian Davis and Burnt Fill Deposit (CWF)

Figure 19. Student Brian Davis and Burnt Fill Deposit (CWF)

The northeast corner of Unit 490N/516E revealed a heavily burned, deeply dug pit containing a great deal of cinder/clinker, charcoal and ash. Only a portion of the pit was revealed and interpreted as a later twentieth century event, perhaps the remnants of a campus bonfire. The feature begins immediately below the topsoil level and clearly cuts through the orange clay fill layer established to date from the 1930s, so it postdates the restoration period. This feature was not extensively documented.

Page 49 Figure 20. Summary map of the 2005 Excavation Block showing all features

Figure 20. Summary map of the 2005 Excavation Block showing all features

Stratigraphy of the Excavation Block

Six major layers of overburden fill were distinguished in the block excavations. These are primarily twentieth-century fill episodes, although they contain a great number of redeposited colonial artifacts that have been displaced from Page 50 their original context. The base of the excavation block is much less clear in terms of its temporal association. At present, it is not possible to determine whether the two very thin, and sometimes indistinguishable layers at the base of the excavation represent a remnant of a colonial deposit, or if all such deposit has been destroyed. These six deposits were largely consistent from unit-to-unit across the excavation block, with minor variations noted below.

Figure 21. Profiles of Unit 498N/508E

Figure 21. Profiles of Unit 498N/508E

Topsoil Layer

The topsoil layer was simply established as the AO horizon, where the sod was removed down to an initial compaction and lightening of the soil profile.

Brown Clay Loam

The "Brown Clay Loam" layer is essentially an incipient AB soil horizon developing, with evidence of leaching and is slightly more compact than the Page 51 topsoil. Although excavated separately stratigraphically, it is essentially an extension of the topsoil, not a separately deposited layer, and can be analytically combined with the topsoil layer as modern. This layer extends to approximately 10-12 centimeters below the surface across the excavation.

Brick Clay Loam

The "Brick Clay Loam" layer seems to be the most recently imported fill to the Wren yard; this is the deposit the natural surface is weathering to form the topsoil. It contains redeposited artifacts, notably brick inclusions that distinguish it from the "Brown Clay Loam" above it. The texture of the Brick Clay Loam is otherwise similar to Brown Clay Loam although it is somewhat more compact. The Brick Clay Loam layer varies from 6-10 centimeters in thickness across the site.

Orange Clay Fill/Orange Clay Fill II

The "Orange Clay Fill" layer is a compact clay fill varying from 20 to 30 centimeters in thickness. The clay appears to be a redeposited subsoil, likely taken from an unknown local borrow source. Artifacts are present throughout the fill, spanning the colonial period through at least 1930, based on a camera flash bulb fragment found in the fill. This accords well with the assumption this fill was imported as the 'capstone' for subsurface work of the restoration work done by the Williamsburg Holding Company to the historic buildings. One unit, 490N/512E contains a designation of "Orange Clay Fill II", based on a feature (Context 16GA-00037/16GA-00038) found within the layer. It now appears that the feature was simply a stain from a rotted plank incorporated within the clay fill. Orange Clay Fill II simply designates the same natural stratigraphic layer, but below this ephemeral feature. No other unit contains the Orange Clay Fill II layer designation.

Dark Olive Loam/Dark Olive Loam B

"Dark Olive Loam" appears to represent the late nineteenth/early twentieth Century ground surface that was likely extensively disturbed by restoration activities. A "Dark Olive Loam B" was defined, mostly because some remnant soil development could be seen differentiating the upper few centimeters of the deposit from the remainder. A very sharp contact differentiates the Dark Olive Loam from the capping Orange Clay Fill. Analytically, however, both Dark Olive Loam and Dark Olive Loam B can be considered the same cultural deposit. The Dark Olive Loam is a more organic, and much less compact, deposit than the clay fill immediately above it. The restoration-era brick drains are all cut into this layer, but not through the clay fill above. Terminus Post Quem dates from the combined Dark Olive Loam place the deposit at no earlier than 1885. The layer is approximately the same thickness as the clay fill layer, averaging approximately 20 centimeters.

Light Gray Mottled Layer

The transition to the "Light Gray Mottled" layer is a markedly more diffuse contact than that between the Orange Clay Fill and the Dark Olive Loam strata. The Dark Olive Loam gradually gives way to a sandy loam fill; this Light Gray Mottled deposit is notably less dense in artifacts, and appears to have less organic content than the Dark Olive Loam levels.

"Layer X"

Layer X was given its mysterious designation, as it is something of a stratigraphic enigma. There is not a clear visual boundary between the lower Light Gray Mottled layer, "Layer X" and the subsoil; however, certain features (e.g., Linear Feature 1, discussed below) appear to be cut into lower Light Gray Mottled, and this level has to be removed further to expose the additional features (e.g., Linear Feature 2). Therefore, a stratigraphic division is logically apparent, but visually not detectable. "Layer X" was defined as necessary by excavating in comparison with depths of adjacent units, and fully exposing the subsoil as defined by the complete absence of cultural material, such as brick flecking, and a uniform, mottled subsoil appearance across the unit. A soil chemistry analysis by student Richard Williams (2005, see also soil chemistry results in Appendix 5) seems to confirm the "reality" of Layer X having a different composition from the Light Gray Mottled layer, as clearly different patterns of element distributions are present when comparing one to the other.

Subsoil